Last month I ended a six-month dry spell, adding two French gaming books to my collection. Each has bibliographical oddities.

The first book is L'Arithmétieque du Jeu de Boston published in Cherbourg. Although no author or publication date is given, secondary sources identify the author as Louis-Guillaume-François Vastel and the date as 1815. Boston is a game of the whist family, discussed here and in more detail in Hans Secelle's recent book From Short Whist to Contract Bridge Toronto: Master Point Press (2020). The book is rare, with copies found only at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France and the Houghton Library at Harvard.

|

| Vastel, Boston |

As is evident from the title, this is a book on the mathematics of the game, a book on probability. Vastel was a lawyer and mathematician and translated the first part of Bernoulli's Ars Conjectandi into French in 1801.

The book is in a lovely, but tight binding. The sewing threads are nowhere visible, so when I collated it, I had to rely on the signature marks.

|

| front board |

| spine |

The book appears to collate 12o: [1-2]4/2 3-204/2 plus three leaves at the end. Numeric signing became common in the 19h century (see the discussion of the second book below); it is the imposition that I find most strange. I have never seen a duodecimo gathered in fours and twos. I commented about the unusual format to my friend J.P. Ascher and he pointed me to a 19th century printer's manual, William Savage, A Dictionary of the Art of Printing, London: Longman et al (1841). There is a large section of imposition diagrams and figure 36 is a half sheet of twelves, with two signatures, eight pages and four pages, as here.

So the imposition scheme was known to contemporary printers, but why would it be used? A more normal scheme would be to have gatherings of six leaves, reducing the number of gatherings by half, and thus reducing the amount of sewing by the binder. Savage cited a number of earlier printer's manuals for this imposition scheme and, unlike Savage, they clarified why a printer might want to use it. I'll mention only one of many examples. Stower, The Compositor's and Pressman's Guide to the Art of Printing, London: Crosby (1808) called the imposition scheme "half sheet of twelves with two signatures, being 8 concluding pages of a work, and 4 of other matter."

Ah! That makes perfect sense. If 8 pages will complete a duodecimo, you could use this imposition to set 4 pages of another book, or some advertising, or any other job work. But, but but--why would you set an entire book this way? It remains a mystery to me.

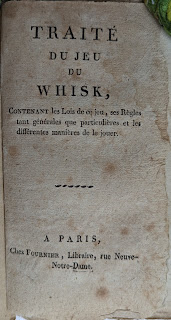

The second acquisition is a translation of Hoyle's Whist into French, published by Fournier in the late 1780s. Fournier published many editions the Almanach des Jeux from 1779 into the 19th century. The Almanach included a calendar and sections on the games of whist, reversis, tressette, piquet, and trictrac. The individual sections were often published separately, as with whist:

|

| Fournier, Whisk |

As mentioned many times in this blog, I do like books in original unsophisticated bindings as here:

|

| drab paper cover |

This, perhaps the commonest method of signing in the nineteenth century and after, is found in only three cases in the sample, two from Paris (1755, 1788) and one from Parma (1795).