Backgammon is mentioned in The Compleat Gamester (1674), a work I discuss in "The Predecessors of Hoyle," but it is really in the 18th century that we get the first works devoted to the game. Interestingly, the first two are poems.

Pax in Crumena is a series of bawdy poems written in 1713 by Thomas Rands, one of which is "A Game of Back-Gammon, Play'd by My Lord and my Lady." In it, the vocabulary of backgammon is used to create sexual metaphor, as is evident in the second verse:

Cinque Trea, the first Night,Only the very curious should seek definitions of the unfamiliar terms in the last lines (NSFW).

Did yield her Delight,

And she made a Point with the same:

Size-Ace the next Throw, or she's ruined quite,

And in danger of loosing the Game:

See how bad her Case is,

For up came Two Aces,

And she is not pleased atall.

Adieu my Delight;

I'm Gammon'd Out-right;

What no more to Night

For my Merkin, my Jerkin, and my Water Firkin?

My Lord, your Two Aces are small.

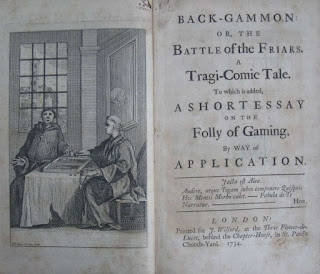

A more substantial effort is Back-Gammon or the Battle of the Friars by Daniel Bellamy, 1734, reprinted in his collection Miscellanies in Prose and Verse, 1741. The book is known for its charming frontispiece, pictured below.

| ||||

| Bellamy, Back-Gammon, 1734. Levy [1650] |

What is more remarkable is that the poem describes the moves in a game of backgammon, certainly constructed for the poem. Nonetheless, it is the first game ever recorded, played between the "dougthy friar" Fabris and his brother friar Vituleo. The description begins:

For the first Onset Fabris did prepare,Rick Janowski has recreated the entire game, which, in modern notation, is:

And Quator Size began the mighty War.

(This was a Service he perform'd by Rote,

And got the * Point that suited with his Coat)

[in a footnote * = The Parson's Point]

Vituleo then, two Sixes by his Side,

Came rushing forward with a manly Stride.

Fabris as yet conceal'd his inward Pain,

Duce Ace oppos'd, but Oh! oppos'd in vain:

Homeward three Pace mov'd, he singly stood,

And stopt directly in Vituleo's Road.

This is my Pris'ner, Sir, Vituleo cries,

And if he meets me once again, he dies.

Fabris VituleoThe play is quite weak by modern standards. Fabris should play 24/22 6/5 for his second move and bar/22 6/5 is somewhat better for his fourth. Vituleo's second move is a blunder (7/5 6/5 is much stronger), as is his third move, which should be 8/5(2) 6/3(2). The position, with Vituleo to play 5-2 is:

1) 6-4 8/2 6/2 6-6 24/18(2) 13/7(2)

2) 2-1 13/10 2-1 18/15*

3) 6-6 ---- 3-3 18/15 8/5(3)

4) 3-1 bar/21 2-1 6/4* 5/4

5) 4-4 ---- 3-3 13/10(2) 6/3(2)

6) 5-4 ---- 5-2

|

| Vituleo (white) to play 5-2. |

Vituleo presses on with Cinque and Duce,All in all, a remarkable bit of backgammon history!

And made the future Blows of little Use.

This for a Rampart he design'd to keep,

Or'e which the nimblests Warrior could not leap.

In safety now the Olive Squadrons move;

In vain the Ethiopian Pris'ners strove,

In Number Three; they could no farther go,

coop'd up within the Trenches of the Foe.

The Friar almost did his Faith remounce,

And lost a tripple Victory at once.

|

| Levy [1537] |

Hoyle's Short Treatises on the Game of Backgammon appears in 1743 and is reprinted throughout the 18th century. I have discussed the publication history throughout the blog and will not repeat it here, other than to show the title page at right. It is the first instructional book on the game of backgammon and the advice, though superficial, has stood the test of time remarkably well.

One other backgammon book appears in the 18th century: Back-Gammon. Rules and Directions for Playing the Game of Back-Gammon, London: printed for H. D. Symonds, and Lee and Hurst, 1798. Symonds was a London bookseller who published hundreds of works from the 1780s into the 19th century. A handful of those books related to games:

- New Royal Game of Connections, 1794, apparently an original work by an unknown author.

- Payne, Introduction to the Game of Draughts, a work first published in 1756 and incorporated into the 1779 edition of Hoyle's Games Improved (see "The Most Important Hoyle after Hoyle)".

- Three editions of Chess Made Easy in the late 1790s, a pastiche of earlier writing on chess, much of which is taken from Hoyle. For example, in Chess Made Easy, we read "In order to begin the game, the pawns must be moved before the pieces, and afterwards the pieces must be brought out to support them." (pp28-9) Hoyle had written in 1744 "You ought to move your pawns before you stir your pieces, and afterwards to bring out your Pieces to support them." (Piquet p55). Hoyle was in the public domain at this point, so there is no suggestion of piracy.

|

| Back-Gammon 1817 reprint |

It won't be surprising then, that Symond's backgammon publication was also lifted from Hoyle. There are a couple of pages of on the origins and rules of backgammon, but the rest of the book is a slight rewording of Hoyle. The book was reprinted verbatim in 1817 for J. Harris, as pictured at left.

Reprints of Hoyle such as Chess Made Easy and Back-Gammon present quite a challenge for the Hoyle bibliographer. The works are nowhere identified as his writing, but are clearly derived from it. None of the earlier Hoyle bibliographers {see "Where Can I Learn More about Hoyle's Writing?") have included these works in the Hoyle canon, where clearly they belong. Why didn't Hoyle's name appear on the title page?

No comments:

Post a Comment