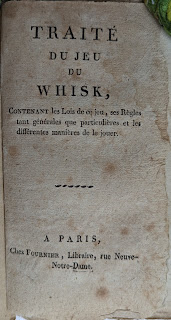

An even dozen books came my way in 2023. I've discussed two of them in the essay "Oddly Imposed. Oddly Signed." I'll write about four more here, ignoring some 19th century books on whist that filled gaps and ignoring some 19th century books in Italian that are on lesser-known card games.

The earliest is a French work on the game of piquet dated 1683. My experience with French and English gaming literature is that small pamphlets appeared treating a single game appeared first in the 17th century. The booksellers learned that those interested in one game were likely interested in more of them, and anthologies replaced works covering a single game. In France, early works on games such as piquet, reversis, and hoc gave way to anthologies such as La Maison Académique. In London, early works on piquet and hombre gave way to The Compleat Gamester and later, Mr. Hoyle's Games.

|

| Piquet 1683 Levy [2191] |

It was a treat to find this late 17th century work, of which only one other copy is recorded. An earlier version of the book was published in 1631 and portions were translated into English in 1651 in a book I discuss in the essay "Piquet, Provenance and a Puzzle." Actually, I'm lying a bit. The first 25 pages of this 43 page pamphlet are on piquet, but it has a couple of pages each on another nine card games. Nonetheless, it is a small (12.5 x 8.7 cm) pamphlet and feels more like one of the single-game pamphlets.

Next is a manuscript on the game of trictrac. I've shared other trictrac manuscripts here, here, and here. As noted on the title page, the scribe copied the book while he was staying in the parish of St. Jean de Brayes just outside Orleans in 1787. The printed book is quite rare with three copies known other than mine, one in Lyon, one in Grenoble, and one Châlons-en-Champagne, Marne. All these cities are several hours’ drive from Orleans, so perhaps there remains another copy closer to Orleans. I wonder if our 1787 scribe was aware of the book’s rarity when he spent hours making his copy.

But the year would not be complete without finding some Hoyle. It gets harder and harder for me to find something new and most of the recent acquisitions have been either cheap books or translations. I've often written about Robert Withy, the author of Hoyle Abridged, or Short Rules for Short Memories at the Game of Whist by "Bob Short". My overview article listed editions known to me in more than ten years ago.

|

| London 1806 Harris Levy [2188] |

More continue to turn up, including an auction find, pictured at left. It is an 1806 "twenty-second" edition printed in London for John Harris, described more fully here. I have seen an advertisement for a "twentieth" Harris edition of 1801, an 1806 "twenty-first" edition printed in Bath, and an 1809 "twenty-second" edition printed in London. They are all different settings of type. It is hard to make sense of the fanciful edition numbering and the fact that 1806 saw books published in London and in Bath. No other copies of this one are known, so I won't much complain about the indifferent condition.

|

| Whist Firenze (1823) Levy [2194] |

Recently, I have done a lot of work on my online bibliography. I have added photographs of books in my collection and have reworked the section covering Hoyle in translation. See here and scroll down to "Continental Translations." A couple of clicks away is a full description of this 1823 Italian translation of "Bob Short" on whist, one of two recorded copies. It is the first of two Italian translations of "Bob Short," followed by another Florence imprint in 1832.

Happy holidays and best wishes for 2024!

.jpg)